Mexborough & Swinton Times – Saturday 13 July 1912

Story Of The Disaster.

The district has been thoroughly saddened and subdued this week by a great colliery disaster in our midst, the magnitude of which is yet scarcely to be realised and appreciated.

On Tuesday morning, at an hour variously estimated at between two and four, the south district of the Cadeby mine was rent by an explosion of terrific force, a deadly, silent tongue of destruction which swept along the main airway and sucked up all human life within range. The terrible and complete nature of the havoc it wrought may be gauged from the fact that of thirty-seven men who went down that district, thirty-five were killed outright, asphyxiated, scorched, burnt and torn to death. The other two wonderfully fortunate men were at the extreme edge of the district nearest to the pit-bottom, and so out of range of the mischief.

The Discovery.

To these men : Albert Wildman, dataller of Ivanhoe Road, Conisbrough, and William Humphries, dataller of 38 Annerley Street, Denaby Main, is left the telling of the tale, which after all is very incomplete. Except that the two men were very near the centre of the disaster shortly after it occurred, and saw the riot and ruin which the explosion brought in it´s train, they have not been able to tell us much more than might have been safely left to the imagination. They were so far from the seat of destruction – nearly a mile – that the blast was reduced to a `puff of air´ when it reached them, but they were both experienced miners – Humphries had been seventeen years in the pit – and they knew what it meant. They cast about uneasily for signs mischief, anxiously they enquired all round the neighbouring district, and then, not without an inward tremor for the ominous silence which had succeeded bore within it suggestions of deadliness calculated to give pause to the boldest, they pushed forward. William Humphries

An Ordeal.

“All honour to these men.” They do not appear conspicuously in the newspaper accounts as heroes, but they were suddenly faced with an ordeal of the kind which heroes undergo. They did their best. They ascertained as an absolute fact that there had been a serious explosion, and that men had been killed. There was no guesswork about it. They went to see.

The Narrative.

I was, luckily, the first Pressman to get told a reliable account of the tragedy which virtually accounted for almost eighty lives, and it was William Humphries who told me the story of an awful discovery in the hideous blackness of a sub- teranean slaughterhouse. He told me in quiet level tones, what he had seen and heard, giving me a plain, matter-of-fact narrative, which was the more impressing because it lacked obvious exaggerations.

He told me how the little party he and Wildman, Joseph Farmer, Jack Bullock, and Deputy Fisher crept forward into the hollow stillness of the graveyard, past the level where the tubs were smashed and the girders twisted till they came upon the body of Martin Mulrooney of Mexborough, a dataller. Half the party went forward and the other half went back to give the alarm, and speedily the colliery above and below was alive with excitement and eager enthusiasm for rescue.

No Chance Of Life.

But there never was any question of rescues. The appearance of poor Martin Mulrooney, stretched in the dust at the end of the storm centre told us that no man could have been within range of that fierce sheet of flame and lived. Still, with the air sweet and good, and the roof apparently sound, a free current of air going right through, a few of the men went on with the desperate hope of finding life somewhere among the shattered ruins. It was a vain hope and a fleeting glance at one of the men recumbent around was good enough for a certificate of death. They were lying were lying all over the gallery, some were in natural attitudes, others in that protective posture which is said to accompany any death by burning, and others like Mulrooney, buried face downwards in heaps of soft dust.

Recumbent Statues.

All were badly burned, some horribly scarred, while others, mercifully spared disfiguration, were merely bronzed, and looked statuesque with their stiff extended arms and their hard solid-looking flesh. In eight cases out of ten, the fire had completely shaved the hair of the victims from their heads, and the burns of those poor fellows was weird and inhuman. All the men, of course, had died of asphyxiation, but their burns would have accounted for a very heavy proportionof them apart from the deadly gas, and in some cases the men were badly cut about the head and face.

Rescue Work Begun.

It would be about six o´clock before the management could get to work on the recovery of the bodies, and the splendid rescue teams attached to the two collieries were down the pit within half-an-hour, while in another half-hour the Wath rescue-station had sent over a motor car full of men and was standing by to send as much assistance as five collieries would be likely to require.

Gathering Of Forces.

Sergeant-Instructor Winch with it, and marshalled the rescue operations. Mr. Charles Bury, the manager of the mine and Mr. Harry Witty, agent of the collieries, sprang up from nowhere. While the former went underground the latter stayed above to superintend the thousand and one details which required instant attention, and to stem the rapidly rising confusion which threatened to overwhelm the officials.

Mr. W.H. Chambers, the managing director of the company was summoned from Newcastle and Mr. W.H. Pickering, Divisional Inspector of Mines, came hurrying up from Doncaster at seven o´clock, with his assistant Mr. Gilbert Tickle, while from the other direction the senior inspector, Mr. H.R. Hewitt, of Sheffield, and the number of official inspectors was shortly made up by the arrival of Mr. H. M. Hudspeth and Mr. H.R.R. Wilson, of Leeds.

The rescue teams got to work quickly and quietly and the ventilation being good and sound their appliances were not needed after the first trial.

A Ghastly Procession.

A Ghastly Procession.

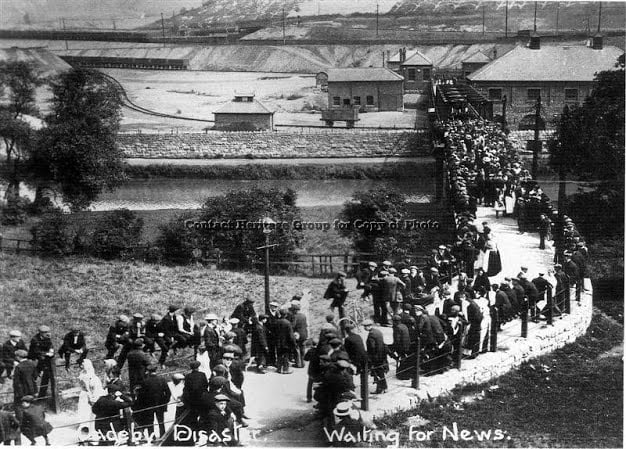

At nine o´clock began the ghastly procession of the dead. Slowly and with reverence they were carried out of the pit-mouth down the two long gantries in full view of the thousands of alarmed onlookers. From seven o´clock until nine the great crowds had gradually accumulated in the roads leading to the pit-yard but all was completely quiet then, for no one knew anything definite.

People merely amused themselves with conjecture and were inclined to regard the rumoured explosion as another of the mare´s nests for which many colliery `explosions´ are often taken as fitting subjects. But the appearance of that first corpse on the top of the tall gantry was enough for the onlookers. A gasp of horror flew around, and swift as the message of the beacon light, the whole of the district was appraised of the horror within their midst.

A Terrible July Day.

A Terrible July Day.

The memory of that terrible Tuesday will live for countless generations. No pen can draw a picture of the horror of it all. The golden sunlight of a warm July day bathed the countryside in an atmosphere of peace and joy, but the ill fated colliery stood out from the hill-side of Cadeby black and stern and sinister and forbidding.

The flags which had floated from it´s headgears the previous day to welcome a King and his Consort, were gone and no touch of colourrelieved the great gaunt tombstone.

All that long black terrible day the bodies took their solemn journey down that awful gantry. Men who went to their work hearty and strong at night, came back stiff and cold at noon, men who gallantly rushed to the rescue at noon were gently shunted twisted and lifeless on the slabs at night-fall. The day was bright and balmy elsewhere.

Death In The Wind.

Here there was a cold shudder in the air, and a whisper of death in the wind. The crowd, which had flocked into the place from miles around in the heat of the afternoon grew and swelled until, at seven o´clock there must have been a great congregation of not less than eighty thousand. Every one was a mourner, and in all that multitude scarcely a sound seemed to be raised. Every where was grey stolid grief, and only when you mingled with the crowd did you detect here the soft weeping of a widow, and there the low fearful mutterings of a father whose strong bright son was no more. Anything more impressive and depressing one could not well imagine.

The Crowning Disaster.

It is a matter of history that the crowning disaster, overshadowing even the holocaust of the morning, came at half past eleven, when a second explosion came along in the centre of the former mischief, and descended amongst the rescuers as they were in the act of taking bodies away, wiped them almost completely out – a fine, gallant force, which included one of the most brilliant mines´ inspectors in the world, and two of his devoted colleagues, a manager of a mine, and four or five leading officials.

The slaughter of the morning was outdone, and the death-roll sprang, in the twinkling of an eye, from thirty-five to seventy-five. The stunning horror of the thing paralysed all movement for a time, and the grief and sorrow, which held that great crowd in one common bond deepened and accentuated. Forty more victims meant hundreds more mourners.

No Respecter Of Persons.

And while we all sorrowed for the poor Dicks, Toms, and Harrys, who had met their deaths, we were shocked inexpressively at the rude impartiality of the Sinister Angel, who, respecting no person, cut off Mr. Pickering, Mr. Tickle, Mr. Hewitt, Mr. Douglas Chambers, Mr. Herbert Cusworth, and, as we then believed, Mr. Charles Bury, every one a man of high repute and inestimable value in the coal-mining industry.

It seemed hard to realise that men who were accustomed to rule and control the wild elements which wreck coal-raising should themselves be struck dead by these rebellious forces. Slowly and by degrees we realised it. The procession of bodies was a little quicker, and now and then we marked the progress of one of these more distinguished victims as we saw the small despondent groups of men escorting their biers.

Why Was It ?

The death of Mr. Pickering was the first to be confirmed, and those who could relapse into anything approaching calmness, on the realisation of the news, did wonder how it was that so gifted a craftsman should have been caught in the toils. Here was lying dead a man of magnificent experience, a man who had run the gauntlet of hundreds of explosions, had forced his way through many hazards, had directed and encouraged and guided in the midst of many perils ; a man who had often risked his life, but never needlessly.

We shall never be given anything like a cogent account of this second explosion. I think, but if there is any reliable narrative to be obtained, we shall want to know whether Mr. Pickering followed his invariable precaution of seeing that the ventilation was kept sound and good, inch by inch, step by stWe cannot suppose that lives were recklessly thrown away on the hands of a seasoned scientist.

Mr. Pickering, of whom the Home Secretary, in his telegram of sympathy, spoke in the highest terms, has long been looked upon as one of the leading authorities on coal mining in the whole world. He has, for a considerable number of years occupied the position of Divisional Inspector for Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, with a break of about two years, during which he did similar duty in India, and quite recently won the Edward medal for a signal act of bravery in supporting a doomed miner while he took the sacrament from a priest.

One of the painful features of his untimely end is the circumstance that he would, in the ordinary course, have been lunching with the King and Queen at Hickleton Hall at the time he was lying amid the ruins of the second explosion.

Fate Of Douglas Chambers.

Another distinct loss is that of Mr. W.H. Chambers young nephew, Douglas, who, after serving a pretty sound apprenticeship under Messrs. Thomsons, Manvers Main, and prior to that at Barrow Main was given the managership of Denaby Main a year ago, while Mr. Charles Bury moved on to Cadeby Main.

The appointment was looked upon as an experiment at the time, but the young man, who is only twenty-eight, justified himself at once, and was doing amazingly well when his career was cut short in this terrible fashion. With a few more years experience, most things would have been possible to Mr. Douglas Chambers.

He was one of the men of the future. Eight or nine months ago he

contracted a very happy marriage at Wincobank, and the grief of hisyoung widow must be inexpressible.

The death of his nephew was the last drop of bitterness in the cup of Mr. William Henry Chambers, who looked a wreck of a man as he came hurrying up at three o´clock in the afternoon, after a journey by forced marches from Newcastle.

Mr. Chambers, who has nursed and built these collieries up to their present magnificence, has made them his darlings, and his nephew was no doubt, very dear to him.

Personal Tragedies.

Mr. Edward Chambers, the manager of Cortonwood, and father of Mr. Douglas Chambers, was on the scene early in the morning, and was hard at work below when he lost his boy.

Another personal tragedy who was contained in the pathetic circumstances was that Mr. Basil Pickering, the manager of Wath Main, who was among the rescuers at the time of the second explosion, and who helped to carry his father out.

There were several remarkable escapes in the second explosion. Sergeant Winch and a man named Lawrence of the Denaby Rescue Party, were the only ones who survived from the Denaby and Cadeby Rescue Teams, the remainder being wiped out.

The Cadeby team, I am told, was practically the same as that which performed before the King at Windsor Park.

Sergeant Winch´s story was brief and plain and graphic. He said that all seemed right, they were all perfectly comfortable. The air was good, and there was nothing to suggest further peril. That being so, he and Lawrence turned back a little way to replenish their lamps, and were about to rejoin their party, when there came the blinding flash of the second explosion, and they were thrown

to the ground. They picked themselves up and ran for dear life. They were practically unhurt, but it was a very close thing. Those two were among the first to make a second attempt at rescue, and, to do them full justice, were undeterred by their grisly experience.

Blissful Ignorance.

Still on the subject of personal tragedies, it is noteworthy that the wife of the doomed Divisional Inspector rode the greater part of the way from York to Doncaster with an evening paper containing an account of her husband´s death before it occurred to her to open it and read it., an instance of blissful ignorance for which it is doubtful whether the lady is thankful. She had been playing a brilliant tennis game at Newcastle for Yorkshire against Northumberland.

What They Missed.

There were several remarkable escapes from the second explosion, if providential diversions can be described as escapes. Three of the younger officials, Messrs. Herbert Williamson, Tom Soar, and Norman Walker were prevented from being in the thick of the disaster by some trifling circumstance or other occurring just a minute or two beforehand. Mr. Witty himself would, in the ordinary course, have been there, and, as soon as the crowd above heard of the explosion, with the wholesale slaughter it had brought in it´s train, they, knowing the bold and enterprising nature of the gentleman, instantly credited him with being among the slain, and so set up a disconcerting rumour.

The fact of the matter was, so far as I can gather, that Mr. Witty stayed at the pit-head in response to the request of Mr. Pickering, that he should remain behind to see to things there. He is supposed to have made a jesting remark to the effect that it was no use them all risking it. I further understand that Mr. Witty was about to call Mr. Pickering out of the pit in order that he might fulfil his Royal engagement at Hickleton Hall, when, before he could do so, he was met with the urgent request, ” Come at once, pit blown up again,” and he went down to help recover Mr. Pickering´s body.

Mr. Bury In Desperate Straits.

The second explosion brought down a very large fall of roof. Mr. Redmayne His Majesty´s Chief Inspector of Mines, speaking to me on Wednesday, admitted it was a very large one, but described it as the kind of fall which usually follows an explosion. It is, however, variously estimated at from one hundred to two hundred tons in weight.

The second explosion brought down a very large fall of roof. Mr. Redmayne His Majesty´s Chief Inspector of Mines, speaking to me on Wednesday, admitted it was a very large one, but described it as the kind of fall which usually follows an explosion. It is, however, variously estimated at from one hundred to two hundred tons in weight.

Many of the poor fellows in the rescue party were caught in this huge fall, and their case was at once hopeless. The others, who were further in advance, were cut off by the fall, and were promptly gassed. These included Mr. Chambers, and Mr. Pickering. Mr. Charles Bury, in whose fate tremendous interest was taken, appears to have been protected by a special providence. He was one of the earliest to be recovered, and he was found to be in a very bad way indeed, though his limbs were protected from the fall by the bodies of two other men which were heaped up over him. He was all but gone when taken to the surgery, but the doctors tackled him gallantly, and fought desperately for a very valuable life. Dr. Forster was particularly prominent resuscitation, though the other doctors who were periodically in attendance – Dr. J.J. Huey, of Mexborough, Dr´s Feroze and McArthur, of Denaby Main – did very valuable work in other directions. Dr. Forster, however, remained with Mr. Charles Bury the whole of the night in the Denaby Fullerton Hospital, working strenuously at the feeble, flickering life to keep it going.

The gravest fears were entertained of this genial gentleman´s condition, but reports were distinctly more encouraging twenty-four hours later. The greatest anxiety was displayed throughout the entire district on the score of the Cadeby manager´s fate, for to lose Mr. Charles Bury meant to lose not only one of the cleverest mine managers in the north of England, but one of the most genial souls who ever passed a merry hour.

Mr. Cusworth Gone.

When the confusion and terror had cleared away, and all was temporarily safe, the decimated little party turned and examined itself, and found itself short of a number of other valuable men. Herbert Cusworth, the capable under-manager of the colliery, was nowhere to be found. Here was another distinct loss. Mr. Cusworth it will be remembered, came to Cadeby from Hoyland Silkstone in May of last year, in succession to Mr. Tom Mosby, who went to Maltby. Since he has been at Cadeby he has done extremely well, and has been a valuable right hand to Mr. Bury, as he was in the cricket field also. Only the other Saturday he knocked up a sparkling sixty-two against Swinton. He was a bluff, but genial and pleasant man, thoroughly interested in all that interested the village, but especially in sport and ambulance work. He was a sound cricketer, and he was also closely connected with the Denaby United Football Club in the capacity of general secretary. Poor Cusworth had gone. That fact was ascertained very early. Such appears to have been the deadly nature of the place that all who were not to be seen in the flesh could be put down as not merely missing, but dead.

Rescue Teams Wiped Out.

Then the whole of the Denaby and Cadeby rescue teams, with the exception of Sergeant Winch and Lawrence, were wiped out of existence, and they included some fine fellows, men who had a fortnight before excited the admiration of a King by their skill in just the kind of work in which they were engaged when they met their doom. There was William Humphries, captain of the Cadeby team, and a nephew of that William Humphries who discovered the original explosion ; the was Jack Carlton, William Summerscales, and the rest, all good men who died fighting.

Another Instance Of Providence.

Another loss is that of poor Sidney Ellis, a third officer in the Ambulance Brigade, surveyor in the colliery, and one of the foremost men in the rescue party. He, with Cusworth, Charlie Prince, Jackson, and seven or eight others, lay buried beneath that huge fall. A cheerful soul was Ellis, and a fine sport. He had a taste for music. Occasionally you could get him to sing at one of the convivials they were always having in that happy and gay village, and he could sing a good song in a good voice. But how abominably he forgot to bring his music. To the writer, who knows some of these men as his own brothers, it is indeed trying work setting down the history of their destruction.

Charlie Prince, who was also hopelessly buried, was one of the smartest and most promising youngsters in the pit, and his death is being most widely mourned throughout Denaby and Mexborough. It is tragic to reflect that there was also a pathetic might-have-been in this case, for I understand that on Tuesday morning, Prince, who is deeply interested in the Boy Scout movement, was taking a troop from Mexborough to Doncaster, en route for Hickleton Hall, there to line up for the approach of the King. Hearing of the explosion, he broke his journey at Conisbrough, and his Boy Scouts went forward. He joined the rescue party, and was one of the first to be killed.

The sympathy of the whole district is with his sister, Miss E. Prince, of the staff of the Mexborough Secondary School, and with his younger brother Walter, who was down the mine at the time, and who refused to leave until he was absolutely convinced that his brother´s plight was hopeless. When the fate of the poor lad became known beyond doubt, the heart-broken brother and sister repaired to their home in Nottinghamshire. Mr. Prince and Mr. Douglas Chambers were both members of the Denaby Tennis Club, which is thus bereaved of two of it´s most valued members.

The Old Brigade.

Another victim who has rendered valuable service in the Cadeby mine and who was killed with the rescue party, is Eli Croxall, another true Denaby-ite, jovial and hospitable, and a thoroughly good fellow. I could go on almost indefinitely through the list, calling attention to the sterling qualities of men who will be sorely missed in the days to come, but the recitals would be too long, and the reading it would make would be too painful to permit myself the indulgence.

Sympathy.

Long before we had recovered from the crushing blow of the second terrific calamity, messages of sympathy began to pour into the place, and were posted up one by one on the railings of the general office. The gracious, kindly message of the King and Queen was the first of all, and then, immediately following the spread of the news of the second explosion, came a long sympathetic wire from the Home Secretary, who referred particularly to the great loss sustained in the death of Mr. Pickering and his colleagues.

There were messages from the Mayors of Rotherham and Barnsley, and afterwards pouring in thick and fast from the West Riding Miners´ Permanent Relief Society, from the Yorkshire Miners´ Association – delivered in person by Mr. John Dixon and Mr. Sam Roebuck, from the Mayor of Sheffield, the Master Cutler, General and Lady Copley, of Sprotborough Hall, the Archbishop of York, the Countess of Yarborough, and many others.

The huge shifting crowds stared dumbly at them, and wondered how they were going to make up to them for the loss of those they held so dear. It is to the lasting credit of the clergy, Established and Nonconformist, that they busied themselves throughout the devastated neighbourhood spreading any spiritual solace and comfort wherever they could. The Vicars of Denaby, and Conisbrough, and Mexborough, with Father Kavanagh of Denaby, the Primitive Methodist minister of Mexborough and others, were to be seen visiting darkened homes all the livelong day.

Huge Gathering.

At seven o´clock in the evening there were more people assembled within a radius of a quarter-of-a-mile of the Cadeby Colliery than there ever were before, or probably ever will be again. The footbridge over the Conisbrough railway station and the lane leading to the glass-works, each converging on the direct lane over the river bridge to the pit-yard, were packed from side to side with people. They scarcely spoke to each other. They just stared in dumb bewilderment at the colliery and it´s environs, and at the occasional corpse which came down the pit gantry.

One Bright Ray.

By the time Mr. Frank Allen, the District Coroner, arrived from Mexborough, to open the inquest, sixty-five bodies had been placed in the pay-station ; but before that, and at about half past seven, there came two visitors who by their presence shed the one bright ray upon the awful gloom of a disastrous day. The King and Queen came to mingle their tears with those of a sorrowing people ! It was hard to realise that their Majesties were actually in the midst of this great debacle of death and ruin ; but such was the case.

They had motored over from Wentworth on the completion of the day´s duties in company with Earl Fitzwilliam and Lord Stamfordham. There were only two cars and they came into the village by way of Hill Top and through Conisbrough. The crowd realised suddenly as the cars slowed up before the colliery offices who the illustrious visitors were, and made a mad rush in that direction. They commenced cheering their Majesties, but the King, with a sublime expression on his face which told of the great grief which consumed him, raised his hand as if in reproof of the mistimed plaudits of the multitude, and the cheering died away, giving place to murmured benedictions.

Royal Sorrow Mingles With People´s Grief.

Their Majesties were received in the colliery offices by Mr. W.H. Chambers and Mr. J.R.R. Wilson, both dishevelled and begrimed by their labours underground, and at the request of the King and Queen these gentlemen supplied them with particulars of the disasters. The King inquired particularly as to the fate of his faithful servants, the Government inspectors, and was tremendously touched by the recital of all that had happened. The interview did not last more than ten minutes or quarter-of-an-hour, but it was extremely painful while it was on.

The King looked pale and sorrowful as he appeared with his Queen at the top of the colliery office steps, and the Queen, without restraint at all, shed the tears of a mother, wife and daughter. Another moment, and they were gone on their way through Conisbrough to Wentworth, but they left behind them in that brief visit a great and lasting impression throughout the whole of the British Empire, for George and Mary had shown the people that they could not only rejoice with them and receive their homage, but could weep with them, and visit them in their affliction.

The visit was epoch-making, and will make a magnificent piece of twentieth century history.

Inquest Opened.

Mr. Frank Allen, during his Coronership has never had thrust upon him such an enormous responsibility as this, but he is a smart man, and he tackled his work very smartly. He got his jury together, and with them viewed the sixty-five bodies in the pay-station, after which he got in as many men as he could to identify as many bodies as they could, and there was an end of things at present.

Mr. Joseph Raley, of Barnsley, of the Yorkshire Miners´ Association, had a few sympathetic things to say, and one of the most touching of his references was to the fact that the list of victims into whose deaths the jury would have to inquire included the names of some who were dear and personal friends of both himself and the Coroner, Mr. Frank Allen, who despite his business-like brusqueness, has a nice way of saying both nice and nasty things, spoke most feelingly of the sorrow and gloom of the district, and of the general state of desolation into which so many families were plunged, in the few words he could trust himself to utter.

The jury list was pretty evenly divided between Conisbrough and Denaby Main, and the following were appointed to serve :-

H.H. Wray ( Denaby ) – foreman, Herbert Dutton, William Isaac Gibbs, John Thomas Asher, John Gillott, William Wilson, William Henry Appleyard, Edward Ball, William Pearson, George William Laughton, Arthur Moody, Charles Raynor,

George Ellis, George Appleyard, and W.A. Lugar.

Inspector Barraclough, of Mexborough, had charge of the inquest arrangements.

All-Night Vigil.

After the several identifications that were brought forward, Mr. Allen went across to the Colliery Offices to sign the necessary death certificates permitting the removal of bodies, but no bodies at all were removed on Tuesday night.

The first to go was that of Mr. Pickering on Wednesday morning when his widow had it conveyed to Doncaster.

The jury and the little army of Pressmen, the latter numbering something near fifty, left the inquest room and the colliery for the night at ten o´clock.

Not so the crowd. They hung around for hours afterwards. Scores of families,

I am told, kept an all-night vigil, doing nothing but simply standing and staring at the pay-station with the dimly-lit windows, behind which sixty-five white sheeted forms lay stiff and stark.

Fortunately it was a hot July night, and the hungering crowds suffered no material discomfort from the weather.

So ended the ninth of July, the blackest day South Yorkshire since Old Oaks and Lundhill.

A Third Explosion.

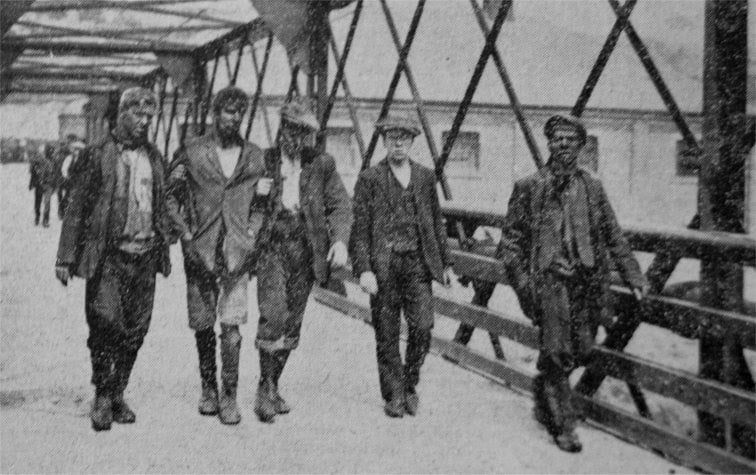

Tuesday’s Rescue Volunteers

When we returned early on Wednesday morning to delve into further details of the cataclysm, it was to be met with the despairing intelligence that there had occurred another explosion during the night, at about half-past-three in fact, and that the rescue workers, in endeavouring to shut off the deadly south district by brick-stoppings in the intake and return airways, had narrowly escaped another catastrophe, for the explosion blew out the stoppings, and they had to scamper for their lives

When we returned early on Wednesday morning to delve into further details of the cataclysm, it was to be met with the despairing intelligence that there had occurred another explosion during the night, at about half-past-three in fact, and that the rescue workers, in endeavouring to shut off the deadly south district by brick-stoppings in the intake and return airways, had narrowly escaped another catastrophe, for the explosion blew out the stoppings, and they had to scamper for their lives

Two of them sustained serious injury, and I believe one of the rescuers, a man named Hulley, who was included in the Windsor Park rescue team, but fortunately not in the one which shared the fate of the forty on Tuesday afternoon, had a wonderfully narrow escape from death, by seven o´clock the stoppings had been restored, and thanks to a periodical inspection of them, were not disturbed for the remainder of the day, though of course there came along an inevitable rumour that more men were entombed later in the day.

An Interview.

At about ten o´clock information was very scarce, and the company of Pressmen chafed sorely at the non-committal attitude of the officials of the colliery, who declined to give information or facilities for getting it, so that the more erstwhile of the correspondents almost broke out into open rebellion, Mr. Chambers was however, good enough to grant me an interview, and with him I met Mr. Redmayne, His Majesty´s Chief Inspector of Mines for Great Britain, and Mr. J. R.R. Wilson, of Leeds, who on the death of Mr. Pickering, became acting Divisional Inspector. They explained to me the present condition of the mine, but frankly confessed their inability to give any forecast of the future conditions or what was likely to be accomplished within, at any rate, the next few weeks.

Condition Of The Mine.

“The management,” said Mr. Redmayne, “are exercising every possible precaution to prevent air from getting to the affected area and by that action they hope to suppress the mischief, whatever it is. The stoppings in the intake and return airways will be periodically examined by bands of skilled men.”

” It is not,” he said in reply to my inquiry,” a particularly hazardous duty, but it calls for the shrewd judgement of trained men. I am departing almost immediately for London, where I shall report fully to the Home Secretary and make arrangements for the Home Office inquiry.”

The Fall Of Roof.

All three gentlemen agreed that the mischief was caused without doubt by explosions, and that the original disaster was not due, as had been suggested by another official, to other causes. ” The second explosion,” said Mr. Redmayne, ” brought down a very large roof fall. How large I cannot say, but just such a fall as explosions do bring down.”

Death Toll Of Eighty-One.

Mr. Chambers informed me that at that time ( Wednesday noon ), there were seventy-one bodies recovered, and there were five living patients in hospital. There were to his knowledge three bodies under the fall, those of Mr. Cusworth, Mr. Ellis, and Mr. Prince. There might be more, but not many more. This number was amended to ten as late as Wednesday night, which brings the death toll up to eighty-one.

The bodies were not likely to be recovered until Thursday, I was given to understand, in the interests of the safety of the mine.

This was all the official information then available, though Mr. Chambers did courteously express a willingness to supply all essential information which was due to the public.

Another ” Might Have Been.”

When questioned by another interviewer, as to the cause of the accident, Mr. Chambers said,” All I can say is it is most mysterious.”

Mr. Wilson, when questioned, was also at a loss for the explanation of the accident. I don´t know whether the public know, he went on, ” but there is absolutely no shot-firing in this pit. Another matter the public might hang on to is the presence of electricity, but there is no chance of this explosion being linked to electricity in any shape. These are the chief dangers and it cannot be either,” and in a brief reference to the fate of his colleague, he significantly replied,” Why I am not among them is because the telephone did not happen to work early enough this morning.”

The Archbishop In The Homes.

There were extinguished visitors to the village during the morning. Viscount and Viscountess Halifax, with two ladies, drove over from Hickleton Hall, and made enquiries as to the latest developments. Mr. J. Buckingham Pope, chairman of the Denaby and Cadeby Colliery Company, arrived from London at 11-30, and just before His Grace the Archbishop of York had motored over from Wentworth in company with the Hon. Henry Fitzwilliam and Capt. F. Brooke, and after leaving a message of sympathy at the Colliery Offices, which was duly posted up, proceeded to the pit-yard in company with Mr. G. Wilkie, the secretary of the company, and the Vicar of Conisbrough, the Rev. W.A. Strawbridge. He held a short but an extremely impressive and touching service in the mortuary and at the pit-head. These were attended by all the available officials and men who were at hand, and prayers were offered for the solace and comfort of the bereaved, while the Archbishop addressed to the men strengthening counsel and guidance.

When he left the pit-yard, without returning to the colliery offices, he made a tour of Denaby Main and Conisbrough, and visited the homes of several of the bereaved families, carrying with him brightness and refreshment, and speaking to many of the poor people words of comfort and hope.

As the visit of the King and Queen had been the one bright spot on Tuesday, so was the visit of the Archbishop the one alleviating feature of the gloom and despair of Wednesday.

After he had completed his round, he had a conference with the Vicars of Denaby Main, Conisbrough and Mexborough, with regard to the funeral arrangements, and some interesting decisions were arrived at.

Great Massed Funeral On Friday.

Most of the bodies were being busily coffined in the pay-station at the time, the colliery company supplying the major batch of coffins, thirty or forty of which appeared on drays early on Wednesday morning. Eight sextons were hard at work on a special plot of ground in the Denaby churchyard, where it is anticipated something like sixty burials will take place on Friday afternoon at three o´clock, all of them, save for a few, which will take place in family graves, in the specially allotted portion.

Most of the bodies were being busily coffined in the pay-station at the time, the colliery company supplying the major batch of coffins, thirty or forty of which appeared on drays early on Wednesday morning. Eight sextons were hard at work on a special plot of ground in the Denaby churchyard, where it is anticipated something like sixty burials will take place on Friday afternoon at three o´clock, all of them, save for a few, which will take place in family graves, in the specially allotted portion.

It has been arranged that the Archbishop shall conduct the first part of what will be a tremendously impressive service in the Denaby Main Parish Church, and that being the case, it is anticipated that the whole of the families of the victims will fall in with the arrangements.

The Conisbrough internments will be taken separately at Conisbrough, and the Mexborough interments, of which there are less than half a dozen, may be included in those at Denaby.

It has been arranged, that if the relatives are agreeable, the coffins shall be placed in the church and seats allotted for each company of mourners.

After the services in the Church, the committals will be taken in various parts of the ground by the Rev. F.S. Hawkes and his assistant curate, the Rev. J. Tunnicliffe, and by the Vicar of Mexborough, the Rev. W.H.F. Bateman R.D., and his assistant curates, the Rev.´s S.H. Lee and S.H. Spooner.

The climax of it will be the funeral oration in the Denaby Main Parish Church on Sunday night.

His Grace is indeed a man of deeds. He is nothing if not thorough.

A Drab Atmosphere.

Wednesday was lacking in general incident, a dull apathy seemed to have descended over the neighbourhood from the very outbreak of the trouble and it required a great deal to lift it. A tour of the village of Denaby Main made up a very dreary pilgrimage. Up one street and down another you saw nothing but the hideous monotony of drawn blinds and women standing discussing the accident in the street, relieved in sinister fashion here and there by the sight of a coffin being transferred from the colliery ambulance into a house or by over-hearing hackneyed street-door philosophy. But on Wednesday morning about half-past-nine, there cropped up one little incident which served to show the real temper of the crowd, hidden as it was beneath the phlegm and lethargy of a stunned populace.

Uncouth Photographer Punished.

Three women were returning from the pay-station, where they had been to identify relatives, and as they appeared in great trouble and were weeping in concert, a callous young Press photographer, scenting only a startling picture, and without any regard for the finer feelings, stepped right into their paths and held his camera in front of their faces while he got a steady `snap´. The crowd promptly smashed his camera, and nearly smashed him.

The Final Offices. Thursday morning.

There was very little fresh information to be had at Cadeby on Thursday morning. But in comparison with the other two days the place was wonderfully quiet and deserted. The explanation was obvious, the families of the victims were busy, quietly making preparations for the burial of their dead on the morrow.

Down at the pay-station a company of nursing women were doing excellent work in coping with the laying-out of the bodies prior to the process of their coffining. When the disaster first broke out the women were at once on the scene together with some auxiliaries from Wath, but they were sent back. They were not wanted then. But they were sadly wanted in the two succeeding days, when the bodies had to be prepared for their grave clothes, and they worked splendidly under the ghastly conditions and suffering the continuous ordeal of unpleasant stenches. Under the sweating heat of the July sun the mortuary attendants had hard work to keep the advance of decomposition in something like decent check, and the pay-station seemed to ooze with the persistent odour of disinfectants. Gradually, however, the coffins received their appointed burdens, and by Thursday afternoon most of them were safely lodged in the homes of the victims.

There is a general air of desolation and idleness about the district, which seems to suggest that there never will be any work at Cadeby colliery. At Denaby colliery, since Tuesday, work has been carried out in a desultory fashion, but, practically speaking, there has been nothing done anywhere.

I am told that it is likely that Cadeby colliery will re-open for work next Monday, but it is quite impossible to say what will be, or indeed, can be, done with the devastated district where lie the bodies of ten men still missing from the mortuary. Those bodies will have to be recovered as early as is possible, consistent with the safety of the mine, after which a tremendous fall of roof will have to be made good, and the whole length of the district covered by the explosion will have to be thoroughly repaired after it has been made accessible by the extinction of the fire. It is hardly likely that for a month or six-weeks at least, there will be any goal-getting in this South District, which bears a sinister name for evermore.

Sorry Time For Officials.

It has been a sorry time for the officials of the Company. They have been racked and riven by desperate relatives, importunate Pressmen, and excited messages from the pit, until they have scarcely known what to do or how to do it. A good deal of the confusion which early set in was doubtless due to the absence in Newcastle, of the president genius, who, however, came as quickly as he could.

Doubtless, if the work of the officials had been classified, things would have gone much more smoothly, but a luckless official setting forth on a mission might, before he could accomplish it, have ten other missions thrust upon him.

It was a long time before the confusion and chaos, even in a well-organised office like this, could be reduced to order.